Tryzub - Rebirth across Thousands of Years

Since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war, a symbol has frequently appeared in Ukrainian news photos, on flags, backdrops, government buildings, and in the banners of protests and demonstrations.

Ukrainian President Zelenskyy during a wartime speech

Ukrainian President Zelenskyy during a wartime speech

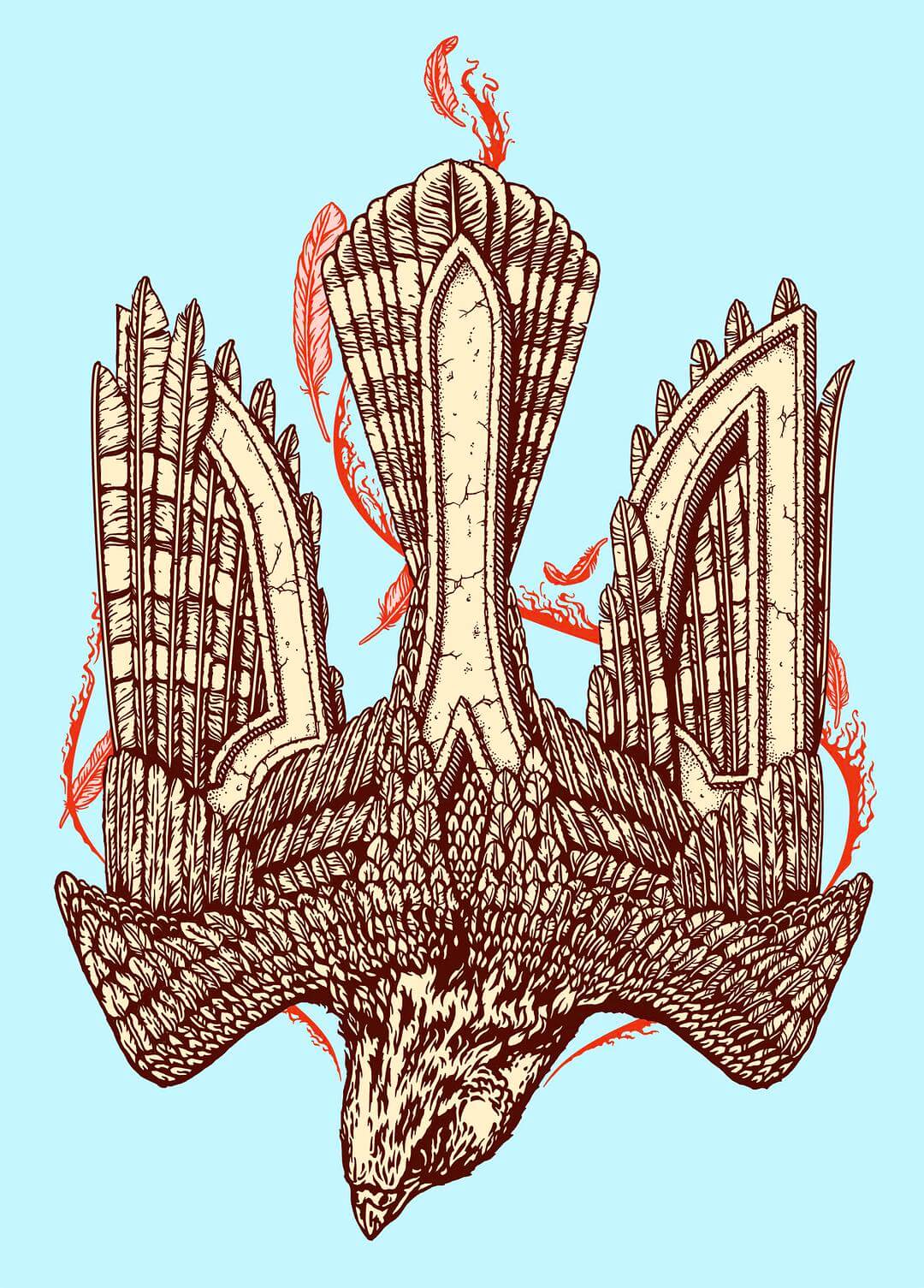

With minimalist lines that are both resilient and dynamic, and a mysterious charm that is unforgettable at first sight, it is the Ukrainian coat of arms, the golden trident (English: Tryzub, Ukrainian: Тризуб).

In recent times, anti-war marches have seen Ukrainian blue and yellow flags waved, and city landmarks illuminated with blue and yellow lights. Many people know that the Ukrainian flag symbolizes the blue sky and golden wheat fields, but what does the Tryzub represent?

Among the complex and ornate emblems like lions, the Saladin eagle, gears, sickles, and stars, the Ukrainian coat of arms stands out with its simple and modern style. It’s hard to imagine that the Ukrainian coat of arms is not a product of modern design; its history spans a thousand years.

The Origin of the Tryzub

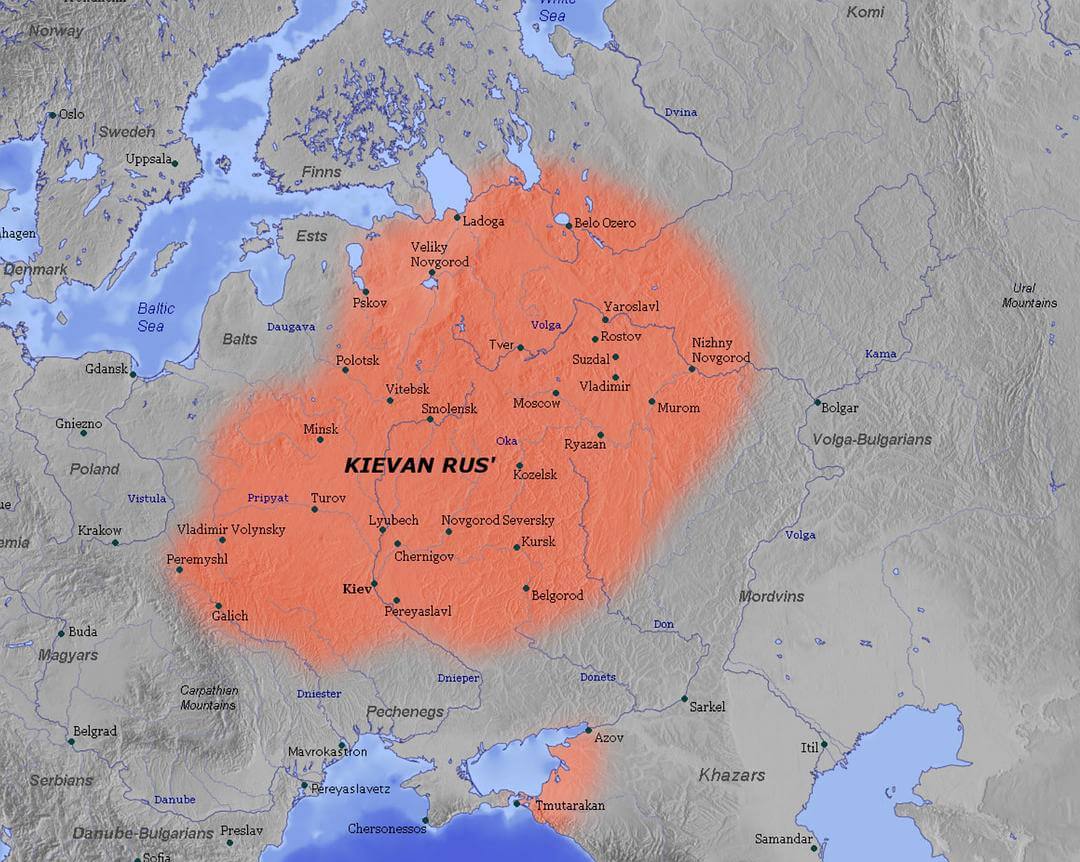

In the 9th century, the Eastern Slavic tribes on the Eastern European steppes were in constant warfare, exhausting each other. The civilization of the Nordic Vikings at that time was far more advanced than that of the Slavs, so the Eastern Slavic tribes invited the Viking Rurik to become their grand prince and resolve disputes through law. Thus, the Rurik dynasty began. After Rurik’s death, his successor, Grand Prince Oleg, strengthened his rule, moved south to capture Kyiv, and established the Kievan Rus’ (882 AD) with Kyiv as the capital.

Kievan Rus’

Kievan Rus’

Later scholars, to emphasize that the capital of this period was in Kyiv, intentionally added the prefix “Kyivan” to the original Rus’ (similar to the way historians refer to Shu-Han or Southern Song), hence the term Kyivan Rus’. Kyivan Rus’ is the common origin of the three Eastern Slavic nations of Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus.

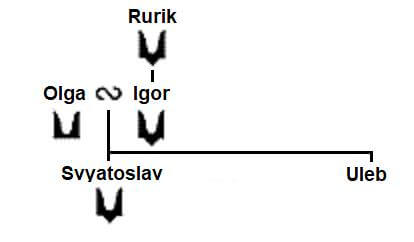

The grand princes of the Rurik dynasty used unique symbols to indicate property ownership, marking them on seals, coins, and weapons.

The grand princes of the Rurik dynasty used unique symbols to indicate property ownership, marking them on seals, coins, and weapons.

The earliest written record of Rurik symbols appeared in the mid-10th century. The Persian scholar Ibn Miskawayh recorded the battle of Rus’ against Barda in 943, describing how, when Rus’ collected ransom, they gave the captives a clay tablet marked with a symbol, allowing them to pass freely.

The Primary Chronicle, compiled in the 12th century by Kyivan Rus’, also mentions: “Olga of Kyiv went to Novgorod and established posts and collected tribute… her hunting grounds spread across all the lands, marked with her symbol and posts.” The “symbol” here refers to the symbols marking the grand prince’s property. The chronicle does not describe the appearance of the symbols, but from unearthed coins and ruins, it is clear that the early grand princes of the Rurik dynasty used a two-pronged symbol, resembling an inverted letter “П”.

Two-pronged symbols used by the first three generations of Rurik dynasty grand princes

Two-pronged symbols used by the first three generations of Rurik dynasty grand princes

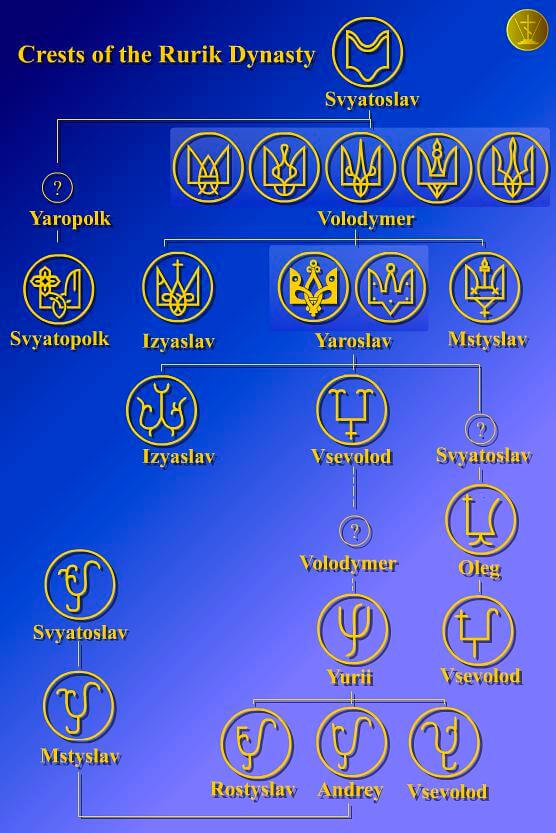

Unlike the coats of arms in Western Europe, where noble coats of arms belonged to the entire family and were inherited without alteration by the eldest son, the Rurik symbols were personal. Starting with the first grand prince of Kyiv, Sviatoslav, the grand princes of the Rurik family would slightly modify the symbols of their predecessors, adding or removing prongs, crosses, dots, lines, and so on, transforming them into their personal symbols.

The early Rurik grand princes’ symbol inheritance

The early Rurik grand princes’ symbol inheritance

These symbols were widely used in Kyivan Rus’—the grand prince’s symbol was stamped on state documents, coins were minted with the ruler’s emblem, and craftsmen branded the grand prince’s symbol on their creations.

The trident-shaped Tryzub symbol was discovered on coins from the time of Vladimir the Great (958-1015, grand prince of Kyiv, often referred to as “the Great,” though not an emperor).

Coins from the time of Vladimir the Great

Coins from the time of Vladimir the Great

Coins from the time of Vladimir the Great

Coins from the time of Vladimir the Great

Vladimir the Great introduced many Byzantine cultural elements to Kyivan Rus’. His grandmother, Olga, was the first Rus’ ruler to convert to Christianity, and he further established Christianity as the state religion. Both the Catholic and Orthodox Churches recognize him as a saint. Due to Vladimir the Great’s reign, the history of the Eastern Slavs became inextricably linked with the Christian faith.

Vladimir the Great built the Church of the Tithes in Kyiv in honor of the Virgin Mary, where he and his wife were also buried after their deaths. The foundation of the church was engraved with the Tryzub symbol.

During Vladimir the Great’s reign, Kyivan Rus’ expanded its territory and reached its zenith. In the people’s memory, Vladimir’s reign was the golden age of ancient Kyivan Rus’, inspiring many songs and folk tales in his honor. Vladimir the Great took the Galicia region from Poland, which later produced several important principalities.

The Church of the Tithes in Kyiv, with the Tryzub on its foundation

The Church of the Tithes in Kyiv, with the Tryzub on its foundation

Does the Tryzub symbol depict a trident? Not necessarily. Kyivan Rus’ was inland, and fishing was not a developed industry, so the trident was not closely associated with it. Most historians believe the Tryzub may symbolize the Christian Trinity. It could also be a highly stylized totem of a falcon, depicting a diving falcon.

Diving falcon

Diving falcon

Coins from the time of Vladimir the Great

Coins from the time of Vladimir the Great

The Disappearance of the Tryzub

The Rurik family’s symbols were used until the mid-12th century. By the 13th century, the Rurik symbols gradually fell out of use. Scholars believe this was because the symbols were too simple, making them too similar to one another and losing the ability to mark personal ownership. Therefore, the Rus’ grand princes gradually adopted Western-style noble coats of arms.

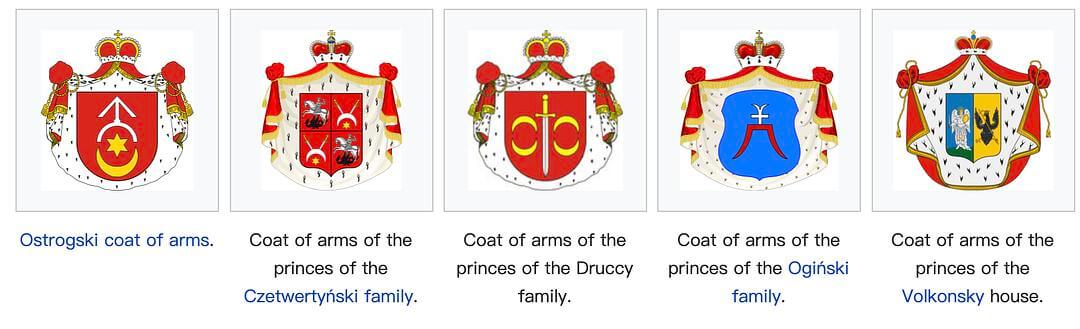

The coats of arms of various Rus’ principalities

The coats of arms of various Rus’ principalities

Vladimir the Great on the Ukrainian 1 hryvnia note, with his Rurik symbol still present

Vladimir the Great on the Ukrainian 1 hryvnia note, with his Rurik symbol still present

Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise on the Ukrainian 2 hryvnia note, with his symbol on the central coin

Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise on the Ukrainian 2 hryvnia note, with his symbol on the central coin

Vladimir the Great divided his twelve sons into various territories, making them semi-independent rulers. His son Yaroslav the Wise took the throne of Kyiv and further strengthened Kyivan Rus’. He established the practice of lateral succession, where the throne passed to brothers before moving on to the next generation’s eldest son (similar to the succession system in Saudi Arabia).

After Yaroslav’s death, Kyivan Rus’ fell into internal strife, with various principalities declaring independence. They were all branches of the Rurik family, ostensibly recognizing the grand prince of Kyiv as their suzerain but effectively acting independently, even waging war against each other. This period of fragmentation lasted for a long time. During this time, the western Rus’ principalities of Galicia and Volhynia merged to form the Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia, which became quite powerful and had more cultural exchanges with Europe, giving rise to the embryonic Ukrainian nation.

In 1235, Batu Khan led the second Mongol invasion of Eastern Europe, sweeping across the steppes and destroying many states. The Rurik grand princes were defeated one by one. The Mongols entered Kyiv, and the last place of resistance was the Church of the Tithes. The battle caused a fire, and the church collapsed under the weight of the people. With that, Kyivan Rus’ fell.

The remaining Rus’ grand princes submitted to the Golden Horde, beginning more than two centuries of Mongol rule over the Rus’. To facilitate governance, the Golden Horde selected one of the Rus’ grand princes to be the “Grand Prince of All Rus’,” who was responsible for collecting the tribute owed to the khan.

During this time, the Principality of Moscow was established, with its grand prince being a branch of the Rurik family. Initially, Moscow was just a small city-state, but over the next hundred years, it gradually expanded its territory through conquests, marriages, and inheritances. In 1328, Ivan I of Moscow was appointed “Grand Prince of All Rus’” by the Golden Horde. Starting in 1389, the Grand Prince of All Rus’ title was inherited by the Grand Prince of Moscow. By this time, the Principality of Moscow had eliminated most of the Rus’ principalities. The Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia was eventually divided and annexed by Poland and Lithuania, and the serfs and citizens who fled from Poland formed the Zaporozhian Cossacks in the middle Dnieper River. The word “Cossack” comes from the Turkic word meaning “free man.”

In 1480, the Principality of Moscow defeated the Golden Horde, ending Mongol rule over Rus’. In 1547, Ivan IV of Moscow was crowned Tsar of All Rus’.

Since the establishment of Kyivan Rus’ in the 9th century, the Rurik dynasty had ruled most of the Rus’ land. By this time, most of Rus’ was under the control of the Rurik branch of Tsarist Russia. The Rurik dynasty continued to rule until the extinction of the line with Tsar Feodor I (1598), after which the Romanov dynasty began.

In 1648, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, leader of the Zaporozhian army, led a large-scale Cossack uprising against Polish rule, establishing the Cossack Hetmanate. Khmelnytsky is celebrated as a liberator who freed the people from Polish bondage. The Cossack Hetmanate was called “Little Russia” by Tsarist Russia, while in Poland, the Ottoman Empire, and the Arab world, it was called “Ukraine.” Ukrainian scholars assert that the word “Ukraine” comes from “u-kraina,” meaning “homeland.”

Bohdan Khmelnytsky on the 5 hryvnia note

Bohdan Khmelnytsky on the 5 hryvnia note

In 1654, the Cossack Hetmanate sought Russian protection against Poland. Whether Khmelnytsky intended to form a military alliance or submit to Tsarist Russia, the result was that Tsarist Russia became the suzerain of the Cossack Hetmanate. The Tsarist state, which had originated from the Principality of Moscow, finally gained control of the Kyivan Rus’ Jerusalem—Kyiv.

For the next few centuries, Ukraine was mostly under Moscow’s rule, while the Cossacks were incorporated into the Tsarist army as free cavalry units, earning merit in campaigns in the Caucasus and Siberia.

Khmelnytsky is widely regarded as a national hero by Ukrainians. The Khmelnytsky Monument in central Kyiv is a landmark of the Ukrainian capital. Although most Ukrainians today view him positively, his alliance with Tsarist Russia is still criticized by some as a disastrous decision for the country’s future. The famous Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko was one of Khmelnytsky’s harshest critics.

In 1721, Peter I was proclaimed Emperor of All Russia, establishing the Russian Empire. During the reign of Catherine II, the sovereignty of the Cossack Hetmanate was gradually eroded. The position of Hetman was finally abolished in 1764, and the Hetmanate was fully annexed by the Russian Empire.

The existence of the Cossack Hetmanate for over a hundred years provided rich material for Ukrainian national thought. The idealized image of the freedom-loving Cossack became deeply rooted in the Ukrainian psyche, distinguishing themselves from Russians and fueling Ukraine’s quest for independence. Although Ukrainians in the east and west were subjected to Russification and Polonization, they still retained a shared Cossack culture and identity.

In the 18th century, during the Russian conquest of Poland, the Ukrainian national revival began to gain momentum. The Russian authorities pursued a policy of cultural assimilation, and in 1876 the Ems Ukaz was issued, banning all Ukrainian-language publications.

The February Revolution of 1917 led to the abdication of the last Romanov ruler, Nicholas II, giving Ukrainians another opportunity for autonomy and independence.

The Reappearance of the Tryzub

After the February Revolution, the Russian Provisional Government was established. On March 17, 1917, the Central Rada (Ukrainian National Council) was established in Kyiv, declaring the formation of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UPR, also known as the Ukrainian National Republic, UNR), which was recognized by the Russian Provisional Government, granting Ukraine autonomous status.

The chairman of the Central Rada, Mykhailo Hrushevsky, was a historian whose ten-volume History of Ukraine-Rus’ was published in Ukrainian, covering the period from prehistory to the 1660s.

Mykhailo Hrushevsky on the 50 hryvnia note

Mykhailo Hrushevsky on the 50 hryvnia note

Hrushevsky saw the continuity of Ukrainian history from ancient times to the present. He argued that the ancient Ukrainian steppe culture from Kyivan Rus’ to the Cossacks was part of Ukrainian heritage, and that the Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia was the only legitimate successor of Kyivan Rus’, countering the official Russian historical narrative that claimed the Russian Empire as the successor of Kyivan Rus’.

Hrushevsky emphasized the role of the native population, bringing depth to the continuity of Ukrainian history. Throughout Ukraine’s long history, resistance to foreign rule was a key theme. During each transition in Ukrainian history, Hrushevsky highlighted the internal factors in Ukraine rather than external ones. He believed that the serfs who fled from Poland were a significant part of the ethnic composition of Ukraine and an important origin of the Ukrainian Cossacks. He viewed Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s and the Cossacks’ uprising against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a national movement rather than a religious one.

In short, Hrushevsky provided academic support for Ukrainian national history and was actively involved in the Ukrainian independence movement, serving as the first head of state of modern Ukraine. He is regarded as one of the greatest Ukrainian historians and a key leader of the Ukrainian national movement, one of the most revered figures in Ukrainian history.

After the October Revolution, the Ukrainian Central Rada refused to recognize Bolshevik control over Ukraine, declaring that Ukraine was only subordinate to a future democratic Russia. Most Cossacks joined the anti-Bolshevik White Army.

In December, the Bolsheviks established the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (UkSSR) in Kharkiv, opposing the Ukrainian People’s Republic. In January 1918, the Bolsheviks began their offensive against Ukraine. On January 22, the Central Rada declared Ukraine’s complete independence, becoming a sovereign state.

The newly independent Ukraine, surrounded by powerful enemies, needed a unifying symbol—the national emblem. Hrushevsky pointed out that Ukraine had never had a permanent national emblem. He wrote several articles in newspapers discussing various symbols from Ukrainian history that could serve this role. Candidates included Vladimir the Great’s Tryzub, the lion of the Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia, the Archangel Michael, guardian of Kyiv, and the depiction of a Cossack with a musket from the Zaporozhian army.

Ultimately, Ukraine’s founding fathers proposed using Vladimir the Great’s Tryzub symbol as the national emblem. On February 27, 1918, the Central Rada declared the blue and yellow flag of the Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia as the national flag of the new Ukraine, and the gold trident on a blue shield as the national emblem.

Ukrainian currency from 1918

Ukrainian currency from 1918

Thus, the Tryzub was revived in modern Ukraine after a thousand years, not as a symbol of royal property, but as a symbol of the land and its people, becoming a symbol of the Ukrainian national movement’s spiritual unity.

Ukrainian Navy flag made in 1918

Ukrainian Navy flag made in 1918

The Soviet Russian government denied its invasion, while supporting the Soviet regime in eastern Ukraine in its attack on the Ukrainian People’s Republic. Ukraine fell into years of civil war, with numerous factions vying for power, including both sides of World War I. Galicia seceded from Poland and joined the UPR, but within a few years, Galicia was re-incorporated into Poland, while the main part of Ukraine was annexed by the Ukrainian Soviet Republic. The red flag replaced the blue and yellow flag, and the national emblem was replaced by the hammer, sickle, and red sun. The UPR became a government-in-exile and continued to use the Tryzub as its symbol. In 1922, the Ukrainian Soviet Republic signed the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR with Soviet Russia, Belarus, and the Transcaucasian Federation, forming the Soviet Union, and Ukraine once again lost its independence. Although the golden trident and blue-yellow flag were banned by the Soviet government, they had already taken root in the hearts of the Ukrainian people.

During World War II, some radical Ukrainian nationalists collaborated with the Nazis to resist the Soviet Union, casting a shadow over the Tryzub.

Modern Ukraine and the Spirit of the Tryzub

In the 1990s, after nearly seventy years of existence, the Soviet empire was on the verge of collapse, and various republics declared independence from the Soviet Union one after another.

On August 24, 1991, following the independence of the three Baltic states from the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian Verkhovna Rada (Supreme Council) issued a declaration of national independence. The blue and yellow national flag was reinstated, but the Soviet hammer and sickle emblem was still retained.

On December 1, 1991, Ukraine held an independence referendum and its first presidential election, with over 92% of voters supporting independence. On December 8, the presidents of Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus signed the Belovezha Accords, declaring the secession of the three countries from the Soviet Union. On December 26, 1991, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR passed a resolution to dissolve the Soviet Union, and the Soviet flag was lowered over the Kremlin.

Ukraine once again restored its nationhood, inheriting the legacy of the 1917 Ukrainian People’s Republic. The national flag, anthem, and emblem from that time were reinstated. Given that the Tryzub had already taken deep root in people’s hearts, there was little controversy during this selection process.

On February 9, 1992, the Ukrainian Verkhovna Rada passed a resolution confirming the gold Tryzub on a blue shield as the small coat of arms. It also stipulated that the great coat of arms would use the Tryzub and the Cossack with a musket as the main design elements, to be officially confirmed through legislation in the future.

In 1996, Ukraine adopted a new constitution, reaffirming the status of the small coat of arms featuring the Tryzub as the nation’s highest legal symbol. The description of the great coat of arms remained consistent with the 1992 resolution (Article 20). Many people believe that Ukraine does not need a great coat of arms and that the small one suffices. Over more than two decades, four drafts for the great coat of arms failed to secure the two-thirds majority vote in the Verkhovna Rada. In June 2021, President Zelenskyy submitted a new design draft for Ukraine’s great coat of arms, featuring the Tryzub, a Cossack, and the lion of Galicia as the main elements. On August 24, the 30th anniversary of Ukraine’s Declaration of Independence, the Verkhovna Rada passed the first reading of this draft, with the final decision to be confirmed after the war.

Draft of Ukraine’s Great Coat of Arms in 2021

Draft of Ukraine’s Great Coat of Arms in 2021

Previously, we mentioned two interpretations of the Tryzub symbol: the Holy Trinity and the falcon. Perhaps a combination of both is the most accurate explanation—the falcon was the totem of the Rurik dynasty, and the grand princes of Rurik were often referred to as falcons in literature. The falcon symbol was simplified into a two-pronged shape and later evolved into a three-pronged form during the time of Vladimir the Great after adopting Christianity.

Between 1860 and 1862, Europe witnessed a debate over the meaning of the Tryzub, with scholars offering various interpretations, including the tip of a Byzantine emperor’s scepter, a crown, the dove of the Holy Spirit, an anchor, a Norman helmet, and the end of a Norman axe. Some even viewed it as a symbol of a sword, as some ancient Tryzub designs resembled the shape of a sword.

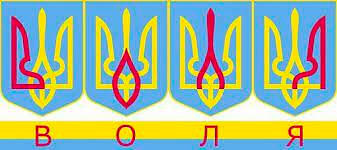

There are also some modern and interesting interpretations, suggesting that the symbol comprises the four letters of the Ukrainian word “воля” (freedom).

воля

воля

Another interpretation sees it as three letters: В (V), О, and Я (Ya), representing Vladimir the Great (V), his grandmother Olga (O), and his son Yaroslav (Ya).

Ukrainian Verkhovna Rada (Supreme Council)

Ukrainian Verkhovna Rada (Supreme Council)

As a national symbol, the Tryzub appears in government settings, flags, currency, and even on people’s T-shirts. Regardless of how people interpret the Tryzub or what it once represented, today it stands for the Ukrainian nation, its wonderful people and culture, instilling a sense of pride among Ukrainians.

This ancient symbol from Kievan Rus has now integrated the free spirit of the Cossacks and the rebellious spirit of Ukraine’s founding fathers. For centuries, Ukraine has been under foreign domination and resistance, facing powers like Poland, Mongolia, the Ottoman Empire, Austria-Hungary, Tsarist Russia, and the Nazis. The Tryzub has become a symbol of fighting spirit against various invaders.

In 1993, Ukrainian sailors paint the national emblem on a Ukrainian frigate at the Sevastopol naval base.

In 1993, Ukrainian sailors paint the national emblem on a Ukrainian frigate at the Sevastopol naval base.

On February 23, on the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Ukrainian footballer Roman Yaremchuk reveals the Tryzub symbol after scoring a goal for Benfica in a UEFA Champions League match, showing support for his homeland.

On February 23, on the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Ukrainian footballer Roman Yaremchuk reveals the Tryzub symbol after scoring a goal for Benfica in a UEFA Champions League match, showing support for his homeland.

Emblem of the Ukrainian Football Association

Emblem of the Ukrainian Football Association

Russians often emphasize the dark history of Ukrainian nationalists collaborating with the Nazis during World War II and attempt to tarnish Ukraine by introducing foreign elements, claiming that the symbol was learned from the Khazars. However, it is well known that Russia’s double-headed eagle emblem was borrowed from the Byzantine Empire. Today, Ukraine still proudly raises the banner of the Grand Princes of Kievan Rus, while Russia’s emblem has become the double-headed eagle of the Roman legions. So, who is the true heir of Kievan Rus?

Vladimir the Great could never have imagined that over a thousand years later, the coins of the Rus’ land would still bear his Tryzub symbol, and the falcon trident flag would continue to fly along the banks of the Dnieper River, uniting the people of this land.

The blue and yellow flag exudes serenity and peace, while the sturdy and powerful golden trident symbolizes bravery. Together, they will continue to inspire Ukrainians to resist unyieldingly. As news of the war spreads around the world, it tells people that Ukraine still exists, and freedom and glory endure.